When Daisuke Matsuzaka came face-to-face with the end of a career that spanned over two decades last week, he smiled.

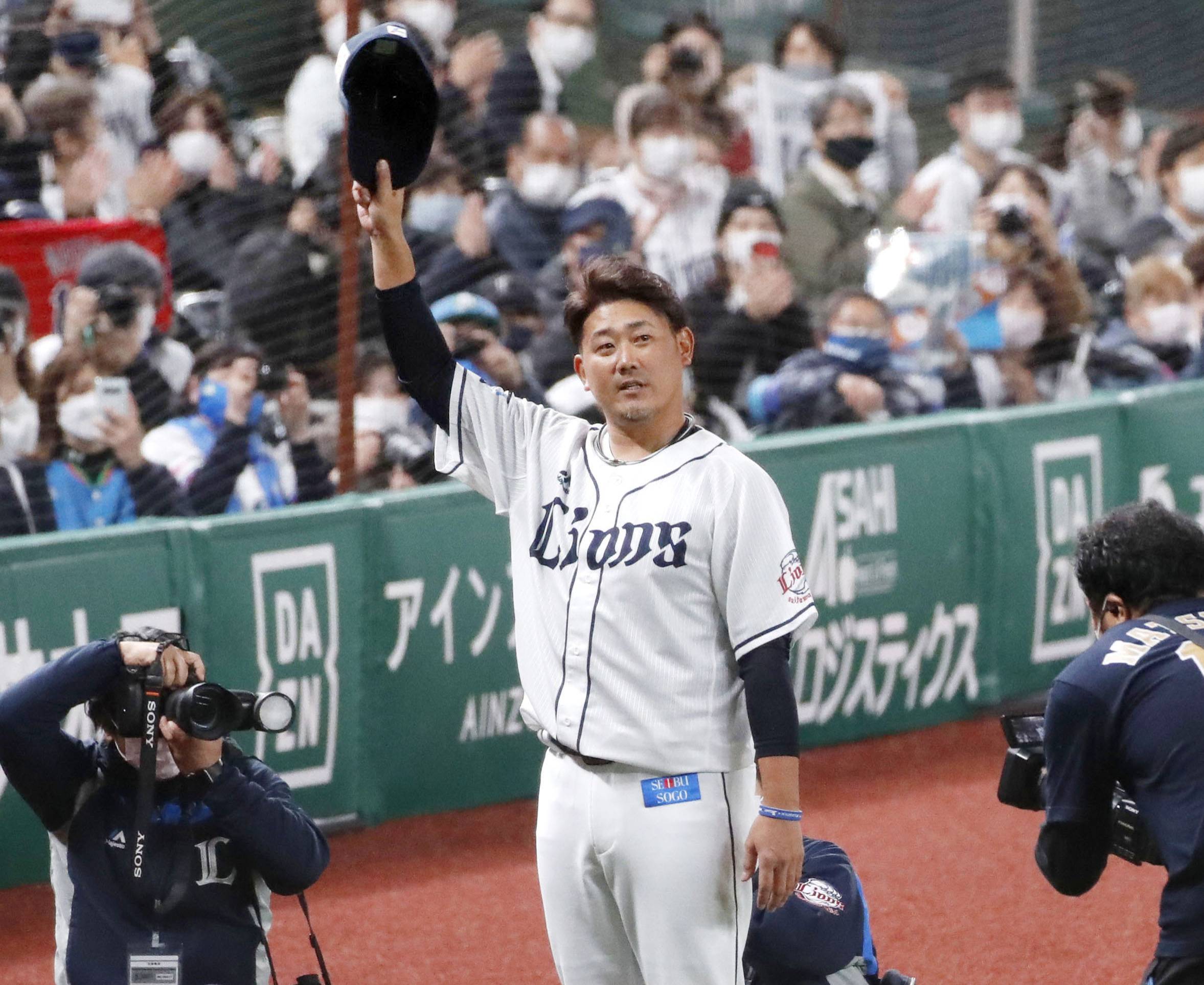

It was more of a smirk at first — perhaps a sign of annoyance after walking Kensuke Kondo on five pitches — but the expression broadened when Seibu Lions pitching coach Fumiya Nishiguchi, Matsuzaka’s former teammate, arrived to remove him from his final start. Matsuzaka bowed and walked off the field as the fans at Seibu Dome, and the Hokkaido Nippon Ham Fighters in the visitors’ dugout, showered him with applause.

There was a similar scene a few days earlier at Sapporo Dome, where Fighters pitcher Yuki Saito faced the final batter of his 11-year career. Saito had reached superstardom as a high school pitcher like Matsuzaka, but failed to emulate Dice-K’s success as a professional. Nevertheless, the “Handkerchief Prince” is still beloved and was given a hero’s sendoff that moved him to tears.

On Saturday afternoon at Tokyo Dome, retiring outfielder Yoshiyuki Kamei, a fan favorite, pinch hit in the fifth inning and jogged out to right field for the start of the sixth, but it didn’t take long to realize something was up. Kamei exchanged quick hugs with his fellow outfielders before manager Tatsunori Hara emerged from the dugout — Kamei was only sent out in order to be removed from the game in a way that allowed the fans to show their appreciation for him.

All things considered, there are worse ways to end a career than walking off the field under your own power to the cheers of the people in the stands.

Retirement comes for all athletes in one form or another. It’s the one thing they all have in common, from the biggest star to the person at the end of the bench, no matter the sport. Some go out in a blaze of glory, like former NFL quarterback John Elway, who retired months after leading the Denver Broncos to a second consecutive Super Bowl title, or Derek Jeter, the famed New York Yankees shortstop who was a key player until the very end. The finale is more brutal for others such as the aging boxer splayed out on the canvas or the once-great basketball player now two to three steps behind everyone else.

The way an athletic life ends can be as unpredictable as the career that preceded it.

That reality lent a certain beauty to the final moments of Matsuzaka’s career, and to those of other NPB players. In Japanese baseball, many retiring players are afforded one last turn in the spotlight — a few at-bats for a hitter or making a start or just facing one last batter for a pitcher.

Those moments are more poignant when it’s a player of Matsuzaka’s caliber or one as celebrated as Saito.

“I started playing baseball when I was around 5 years old,” the 41-year-old Matsuzaka said. “So you could say it’s been my life.”

Matsuzaka’s body didn’t quite cooperate during his finale. The right-hander had not pitched in an official game — on the top team or the farm — since 2019 due to injuries. The complications he still felt after undergoing cervical spine surgery last year led him to announce in July that he was calling it a career.

“I thought it would be difficult to continue because of my condition,” Matsuzaka said during his retirement news conference prior to last week’s game.

He was a shell of his former self, almost shockingly so. Matsuzaka lacked the finesse he once used to nibble around the plate during marathon half-innings at Seibu Dome, Fenway Park and numerous stadiums in between, and barely moved the needle with a fastball that topped out at 118 kph (73 mph).

That was the reality on the mound. But what many fans watching saw was the same long and deliberate wind-up — the arms bent over his head as he gripped the ball, the three to four second pause and finally the delivery — that was quintessential Dice-K, even if the pitches weren’t.

It was enough to bring all the old memories flooding back. There were undoubtedly many watching who instead saw the Monster of the Heiwa Era, who willed Yokohama High School to the Summer Koshien title with a legendary performance during the 1998 tournament. Others may have seen the young fireballer who wore the No. 18, the ace’s number, for the Lions.

As North America began to awaken, there was a wave of missives on social media from fans who remembered spending many long afternoons watching Matsuzaka work the corners and both strike out and walk batters in bunches.

He was deserving of the fanfare.

Matsuzaka won everywhere. After leading Yokohama High School to the title at Koshien, he helped the Lions win the Japan Series in 2004, was part of a World Series champion with the Red Sox in 2007 and on the Japan teams that won the first two World Baseball Classic titles in 2006 and 2009.

He earned the Sawamura Award in 2001 with the Lions and was an 18-game winner for the Red Sox in 2008. Injuries slowed him down after his return to Japan in 2017, though he was the Comeback Player of the Year in 2018.

“I was more likely to give up hits during the latter half of my career,” he said. “It was tough, but I was able to make it this far.”

Was the Matsuzaka of old on the mound last week? Yes and no. He was a shell of his former self, but his presence — and the familiar No. 18 on his back — meant the old Dice-K was on everyone’s mind. Through the memories he stirred up, Matsuzaka, in the most mortal moment of his athletic career, was able to attain a type of immortality. He will never be forgotten, and the forgettable five-pitch walk in his final moments on the mound ensured that in its own way.

Matsuzaka, Saito, Kamei and others in Japanese baseball were able to retire, not through a press release or by being cut in the offseason, but by competing in front of the fans until the very last second.

Matsuzaka and Saito stepped on the mound again. Kamei took an at-bat and got to take his position in the field. The Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks’ Yuya Hasegawa, a former Pacific League batting champion, went out diving headfirst into first base trying to record an infield hit.

Stories that end like Elway’s are the exception in sports. The ending is sometimes uglier, if it happens on the field of play at all.

Japanese baseball stars don’t usually go out in a blaze of glory either. There is something to be said, however, for an athlete being able to walk off the field with their head held high and everyone in the moment celebrating a career well played, rather than regretting one that went on for too long.

Many Japanese baseball players get those moments, and in a world where athletes don’t often get the storybook ending, it’s hard to write a better one than that.

In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever.

By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

Source : Baseball – The Japan Times