New York – Major League Baseball’s first work stoppage since a strike wiped out the 1994 World Series could drag on long enough to jeopardize the start of the 2022 season.

On the day team owners locked out players upon the expiration of the collective bargaining agreement, no talks were scheduled and things were testy between the two sides, even though both said they could return to negotiations at any time.

MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred announced the lockout shortly after midnight on Thursday, calling it “the best strategy to protect the 2022 season.”

“The lockout is part of the process that’s designed to move the parties toward an agreement,” Manfred said.

But players were clearly irked that MLB.com removed the names and images of all current players from its news content section, and replaced images of players on roster pages with blank silhouettes.

Many players responded by changing their social media avatars to silhouettes adding the caption “#NewProfilePic.”

Manfred, speaking Thursday to reporters in suburban Dallas where talks had broken up on Wednesday, said the aim of the lockout was to bring a sense of urgency to negotiations.

“People need pressure sometimes to get to an agreement,” he said. “Candidly, we didn’t feel that sense of pressure from the other side during the course of this week, and the only tool available to you under the (National Labor Relations) Act is to apply economic leverage.”

The lockout brings a halt to free agent transactions, bars communication between teams and players who are in the union and prevents players from using team facilities.

“Since MLB chose to lock us out, I’m not able to work with our amazing team physical therapists who have been leading my post surgery care/progression,” New York Yankees pitcher Jameson Paillon posted on Twitter.

MLB Players Association executive director Tony Clark called the lockout “drastic and unnecessary.”

He also said the “Letter to Fans” posted by Manfred in announcing the lockout contained “misrepresentations.”

“It would have been beneficial to the process to have spent as much time negotiating in the room as it appeared was spent on the letter,” Clark said.

Even with offseason operations shut down, it won’t be until the end of February, when preseason games are set to be played, that both sides begin to feel a major financial pinch.

The $10 billion industry will take a bigger hit if no deal is done before the scheduled start of the regular season on March 31.

“It’s my hope and expectation the parties will get back to the table and get an agreement done,” Manfred said. “Speculating about drop-dead deadlines at this point, not productive, so we’re not going to do it.”

Fans, whose ticket and souvenir purchases finance the clubs and payrolls, spurned MLB after a labor fight left the 1994 season unfinished. Attendance plunged in 1995 as did television viewership. Some people bought tickets only to boo both teams.

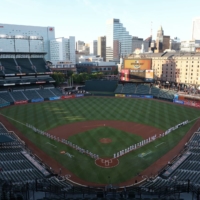

Players and team owners alike know they risk alienating fans again just one season after spectators were welcomed back into stadiums under strict COVID-19 protocols.

“It’s not a good thing for the sport,” Manfred admitted.

In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever.

By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

Source : Baseball – The Japan Times